The Securities and Exchange Commission regularly fills its homepage with glorious facts—data illuminating how much executives make in comparison to their employees, statistics about the value of houses bought by the wealthiest businessmen. It’s quite fun to count and compare how many zeros each value ends in before my finger runs off of the page. But here’s a better game to play: look for statistics based on gender. You won’t find any. When the Securities and Exchange Commission calls out high-ranking business executives for making too much money, it might embarrass a few suits and loosen a couple ties, but it’s nothing anyone didn’t expect. Yet, calling out companies—financial firms, hospitals, fortune 500s—for paying women too little would crack open one of the most pressing contemporary issues.

Over a half-century after President John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act of 1963, the continued gap between what women and men earn has defied every act to close it. The gap in income based on gender may be, as some claim, a result of “women preferring lower-paying industries” or “choosing to take time off for kids” (New York Times). Yet, as Claudia Goldin, a labor economist at Harvard has found, “this gap persists for identical jobs… female doctors, financial specialists” (New York Times).

Although we may be quick to point fingers at men, the gender pay gap stems from an often overlooked phenomenon and a long established culture. It’s not that men are intentionally attempting to discriminate against women or that they don’t want women to succeed. Most claim that they do not have a gender problem themselves; they assume that it “must be some other guy who does the unequal paying business” (New York Times). The cause for unequal pay lies in deeply rooted cultural norms and their unconscious effects. The well-established myth is that women simply do not ask for pay raises. However, in a 2017 study, Do Women Ask?, it was discovered that women do in fact ask for raises as much as men—they are just turned down more frequently (The Cut). Because of the male executives dominating the environment of many workplaces, pay negotiation becomes an area where women are fearful of stepping in—let alone navigating through, causing their proposals for more pay to be less confident than men (InStyle). While men are taught not to take “no” for an answer, women are taught to accept it and move on. In fact, rather than renegotiating, the main reason women leave their jobs is in search of a higher salary (Quartz).

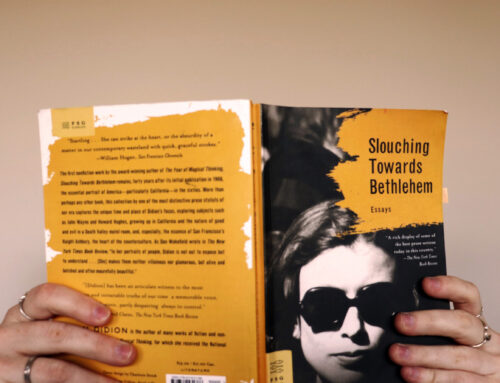

So, what if women did not have to ask for that much awaited pay raise? What if they were handed a gleaming, crisp paycheck with more money than their male counterparts? That’s exactly what Ms. Monopoly brings to the table.

Hasbro Game Company recently launched a new version of the iconic board game that celebrates female trailblazers and is the first board game “where women make more than men” (USA Today). The front of the box captures a woman with a sassy stance and steel-colored blazer, gripping a to-go coffee cup. Jen Boswinkel, senior director of global brand strategy and marketing for Hasbro notes that “with all of the things surrounding female empowerment, it feels right to bring Ms. Monopoly to the table” (USA Today).

Unlike the classic game, women will be able to collect 240 Monopoly bucks when they pass “GO.” Alternatively, male players will be handed the typical 200. But, that’s not the only variance. Instead of buying property, players will invest in inventions launched and promoted by women—things like WiFi and chocolate chip cookies. While Ms. Monopoly strives to give women the pay they rightfully deserve, it does not properly address the causes of the gender wage gap. Some critics question the message which this game is sending to players and audiences. Does the rule of automatically giving women more money when passing “GO” suggest that women are not as productive as men and need to be overcompensated? Christine Sypnowich, head of the philosophy department at Queens College, notes that “it’s unhelpful to portray women as needing special advantages.” This game gives women an advantage from the start, which assumes that instead of relying on their own capabilities, they need a “head start” and outside assistance. Meanwhile, in modern workplaces, men and women begin the race simultaneously, and while some women pass the finish line first, they are still compensated less than the men behind them. Perhaps this is the reality that should be depicted by Monopoly.